Executive Summary

As this document enters its second decade, Gordian’s data continues to reveal unassailable truths about the state of facilities in higher education. In many regards, these truths are also indicators of the health of North American colleges and universities. The academic quad and the stately buildings surrounding it have long been the image of higher ed campuses carried in most people’s minds. The place is inseparable from the educational enterprise.

Things are different now. Lab science and agricultural research is still happening on campus, and gameday would be challenging without a place to gather. But the level of activity on many of today’s campuses is down, and the traditional notions of what a campus is and what it could be are evolving. Employees work remotely. Class sometimes happens without a classroom. Research takes place just as often in a student’s room as in the library. The amount of space needed for the same number of students appears to be shrinking. And if the campus has fewer students than it once did, the activity drop is even more evident. As a result, what we do with existing spaces and how we change our approach to investing have become urgent matters.

None of this is revelatory, or even universal. But the data continues to show us that what we are feeling about campus facilities is true. Facilities portfolios require attention like they always have, but the facilities themselves are not utilized or in some cases even needed in the same way. The choices about what to do with existing space, which historically revolved around assumptions that campuses would continue to grow in their existing form, stopped being automatic and obvious long ago. At the same time, these assets continue to age and the inevitable downward shifts in student population are less than three years away, according to professor Nathan Grawe’s work regarding the impending demographic cliff. These two factors, along with many others, represent immense challenges for institutional leadership.

Analysis of Gordian’s database of 43,000 campus buildings, 1.1 billion gross square feet of space and more than $13.5 billion in capital and operating budgets underscores the enormity of these complex, interconnected challenges.

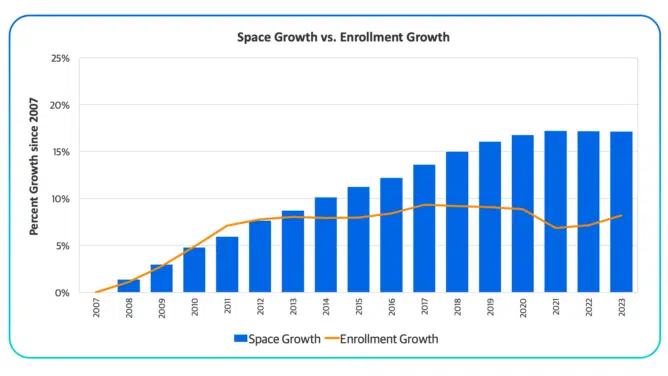

- Space growth has remained flat for the third year, marking a real signal that institutions are recognizing the importance of restraint in the face of countless indicators about the future.

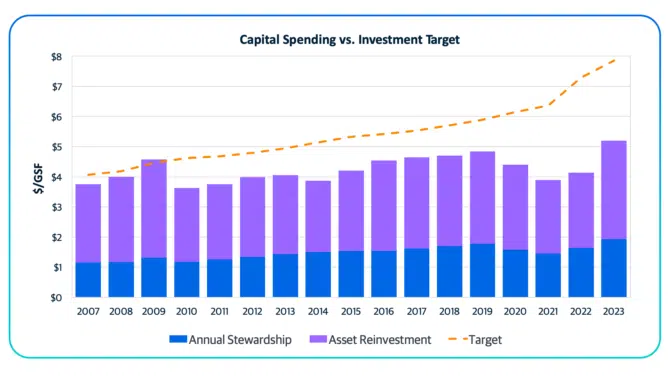

- Institutional investment in existing buildings has rebounded with growth of 33% over the past several years in response to need, but inflationary pressure and increased wages accelerated the cost to care for existing facilities by nearly 20%, leaving a continuing yawning need.

- The pandemic presented an opportunity to alter service expectations and rein in costs going forward, but service quality appears to be declining for the first time in a decade.

- Facilities leaders suggest that finding talented staff is their greatest challenge, and without people to care for a facilities portfolio, the properties age more quickly.

Investment in existing campus buildings has grown by 33%

The last point on the list is the subject of our deeper dive this year. Staffing challenges since the pandemic have made headlines across many industries. A looming shortage has been on the horizon for some time as fewer people enter the trades and existing employees approach retirement. This trend has accelerated in higher education as people have migrated to higher paying jobs in other sectors. The implications for current facilities performance and their future stewardship costs are tremendous. Yet there are some creative efforts in the works to overcome these hurdles.

There are plenty of positive signs that the higher education industry is awakening to the challenges ahead. The campus communities that will thrive into the future are those that move quickly and strategically to avoid the negative impact of those challenges.

Join us for a robust discussion of this report’s findings and find out more about our campus database in this free webinar.

After a decade of expansion outpacing enrollment, the ratio of space-to-enrollment growth continues to stabilize. Current and emerging enrollment challenges, coupled with the real availability of free capital for many schools, have impacted institutions’ willingness to expand. While enrollment has rebounded across the board since hitting a low point during the pandemic, the looming traditional-aged enrollment decline and demographic cliff coming in 2026 mean that any future increases to the student body will quickly be offset. This nexus of circumstances has added gravity to conversations about overall space and ongoing investments. These decisions transcend facilities. They’ve entered the realm of financial (in)stability.

Misalignment between the existing campus footprint and the shrinking need for physical space embodies incredible financial risks. Minimally, these spaces require basic care to preserve them as assets. Continuing such care means committing resources that are increasingly strained if they are available at all. These unused spaces, and the effort and resources expended to maintain them, may serve as a stark symbol of an institution’s diminished influence in a changing world. Often, this produces a circular effect. Students, to say nothing of donors and the broader community, may view these vacant spaces as a reason to enroll or give elsewhere, accelerating campus decline.

Professor and author Nathan Grawe was the first to identify the impending demographic cliff in his 2018 book, “Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education.” Grawe has continued contributing his insights and analysis to the conversation since. He and others have identified a notable pattern: The demographic cliff does not apply everywhere. The most highly selective schools and the great percentage of flagship public research institutions benefit from a perceived value that will continue to draw students and top-tier faculty. The attraction of the best and brightest to established educational brands will, if anything, accelerate the reduction in students available for attendance at the remaining institutions. We are seeing this pattern play out already, with research institution enrollment up 19% since 2008.

Meanwhile, enrollment at most master’s schools has returned to 2008 levels after a 7% climb over the previous 15 years. The situation is starker at baccalaureate colleges, where enrollment is now 2% below 2008 levels. Demographic hurdles are no longer a problem to solve tomorrow. They are a real and present existential danger that must be addressed today. Inside Higher Ed reported that during the 2023 calendar year, 14 colleges and universities had closed, another was effectively closing with no new classes scheduled and seven others were either purchased by or merged with other institutions.

Baccalaureate enrollment is now 2% below 2008 levels

College and university leaders are doing the hard and important work of balancing their ambitions for the physical campus against the realities of shrinking enrollment. This signals an understanding that limited dollars must be focused on stewardship of existing facilities. In extreme cases, leadership must be open to considering space consolidation. Higher education’s current moment, and its attendant trends in space, capital and enrollment, demand it.

In the fall of 2023, the American Council on Education and the Carnegie Foundation announced the intention to make fundamental changes to the methodologies used to classify colleges and universities for the first time in five decades. The new system is designed to be more transparent and reduce the inherent competitive value bias toward research and highest attained degree. Commencing in 2025, the changes will create multi-dimensional groupings that break away from the narrow baccalaureate/masters/research framework that has been utilized in the State of Facilities report since its inception.

While the existing framework remains in place today, we are excited to explore how these changes might enhance our analysis and positively enhance the value of our work to readers. If you have thoughts about this change and its impact on our work, please contact us at [email protected] to share them. For more information on the new classifications, visit the American Council on Education website.

Following the pandemic, campus investments appeared primed to follow the same trend they did in the wake of the Great Recession. That is to say, it was widely expected that these investments would not return to pre-pandemic levels for at least six years. However, a remarkable shift occurred in 2023. Investment levels grew more than 26% year-over-year and by 33%, a full third, since 2021. Spending on existing facilities now exceeds that of fiscal year 2019. This spending increase suggests that colleges and universities now recognize the value of physical assets to the campus experience. That recognition is notable.

Investigating further, this investment increase appears in both the categories of annual stewardship (dollars set aside every year for this purpose) at 17.7% and asset reinvestment (one-time capital dollars focused on existing buildings) at nearly 31%. The spending balance differs from one campus to the next, but growth in both categories indicates a broad-based commitment to this business purpose.

Enthusiasm for the impact of this investment is dampened by inflationary pressure so extraordinary that spending continues to fall short of addressing ongoing needs. The investment gap has existed since the Great Recession and has been no narrower than 16%. During the pandemic’s darkest days, the gap exploded to a harrowing 43%.

The significant gains of the past year have reduced the spending shortfall to 34%. That’s an impressive improvement, yet it still leaves the shortfall nearly double what it was only five years ago. One in every three dollars of need is going unmet. That means a significant ongoing growth of asset renewal needs – the backlog of work that must be done to sustain the campus to meet community expectations. Higher education’s post-pandemic recovery is remarkable and worthy of celebration. Clearly, campus leaders acknowledge the need for facilities investment and are confronting the issue of facilities stewardship. For this courage, we offer them praise. The challenge moving forward is for institutions to strike a delicate balance between ongoing investments into campus and shrinking the demand for such investments through reducing service or removing assets. These are often emotionally fraught decisions, even for the most practical campus leaders. We must become comfortable with discomfort because that’s what the moment demands.

See how Gordian can provide the data and insights you need to build an informed facilities capital plan that aligns your institutional mission with your physical campus.

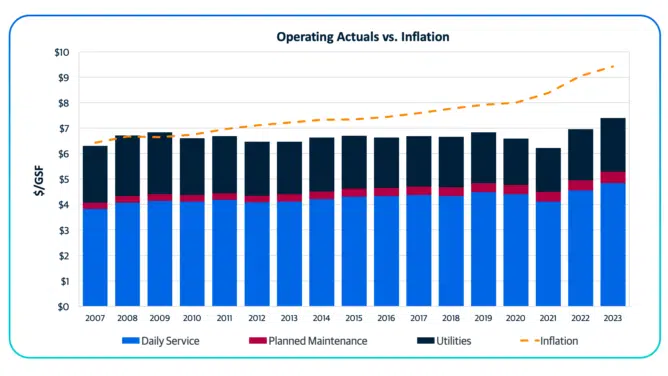

Facilities operational budgets have been remarkably predictable over the last four years. While the buildings remained and had to be kept operable when campuses emptied during the pandemic, schools doubtlessly saved on operational and utilities spending. There were budget cuts, many of them painful, but much of those were ultimately offset by federal support. In all, operating budgets (despite a recent uptick) have been relatively stable. Costs, conversely, have not.

There are good reasons why a budget might not grow at the same rate as expenses. Reducing utility consumption is always a great way for schools to minimize expenditure. Improvements in technology or targeted training can make work less complicated, reduce time spent and increase productivity of the team members. And the pandemic was an opportunity to overhaul service levels. Thus, it is difficult to see just from macro data whether there have been significant impacts to campus due to these reductions.

Institutional operational expenditures grew on average a mere 0.65% annually between 2010 and 2019. All of that gain was lost by 2021, and inflationary pressure increased costs by 26% over that time frame, at a pace of roughly 2.2% per year. Despite notable gains in minimum compensation across many campuses since 2020, there remains steady reporting of unfilled positions due to hiring freezes or simply because it has become extraordinarily hard to find top talent, a challenge that has grown in importance year after year.

A lack of resources and people to use them accelerates campus aging, routine wear and tear, and the ultimate decline of building systems and components. On campuses without adequate recurring capital investment, the backlog of real replacement needs expands at an even greater pace if the operational team is unable to provide the necessary ongoing maintenance and care that is expected for building elements to reach their full life, let alone beyond it.

Operating budgets, overall, have climbed more than 9.5% since 2019. However, minimum wage increases are eating up much, if not all, of that increase. Meanwhile, the cost of buildings supplies and construction services is up over 19% during that same window of time, according to Gordian’s internal analysis. Buying power has effectively declined.

The reported increases in 2023’s operating spend are cause for excitement, and all involved in those increases should be applauded for their efforts. But enthusiasm must be tempered by the real threats that understaffing and underinvesting in operational teams represent to the performance and life of building systems. Fortunately, there have been few reported instances of building system failures that posed a real risk to life. While disruptions to program performance are common, it is only a matter of time before thoughtful leaders will rightly raise concerns about the risk to human activity.

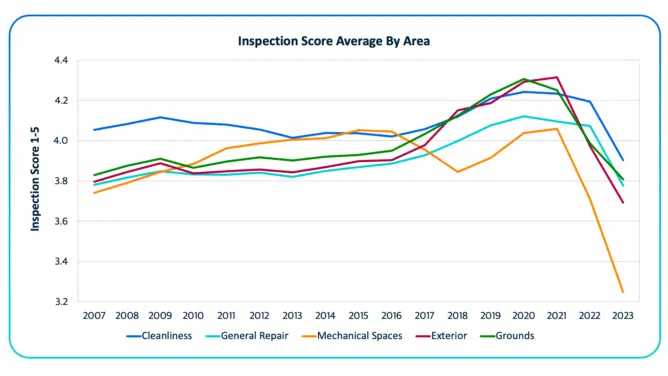

Each year Gordian provides the opportunity for schools with whom we work to undertake a qualitative inspection of several facilities elements (Cleanliness, General Repair, Mechanical Spaces, Exterior, Grounds) on a simple five-point scale. This inspection is not designed to be as rigorous as those implemented by third-party specialists in any given profession. It is also not designed to overlap specifically with APPA’s standards in a number of disciplines. Rather, the inspection is ideally used as a local trending tool to report on the trajectory of efforts to improve service delivery on campus. This variation and lack of universal discipline is also why it has not appeared in previous editions of this report. While this scoring metric is tracked broadly across the database, as is done with most metrics, it has never been one which yielded much universal value. Until now.

Over the last several years there has been a remarkable shift in our survey results, particularly in the area of mechanical spaces. The pandemic brought a great number of changes we have outlined already, but those changes have mostly led to anticipated concerns. In this data we are now seeing a new, unexpected outcome: A decline across the board in scores for each area of inspection.

Negative operational trends have led to degraded facilities and spaces

This decline points to a widespread shift in the quality of building care and the performance of building systems. To be fair, some scores have simply returned to where they were 15 years ago or more, after steady increases around the start of the decade, across an 8 or 10% variation band. But exterior scores have dropped 15% and mechanical space scores have fallen 20%. That is a meaningful degradation. Drops in the exterior score often mean that things are not as well kept, that building envelopes and the grounds around the buildings are showing greater deterioration. Such a precipitous drop in mechanical space score indicates obvious leaks, failed or failing equipment and a general repair decline are more prevalent. With allocated money not stretching as far as it used to and fewer people on the ground delivering services, such poor performance is inevitable.

Not only are we seeing concerns regarding input metrics, but we also see concerning outcomes. Too often the results of input analysis can indicate only what might happen in the future, but this data indicates that negative trends in operational measures (budgets or staffing metrics, for example) are in fact leading to a degradation in the product that facilities organizations are delivering.

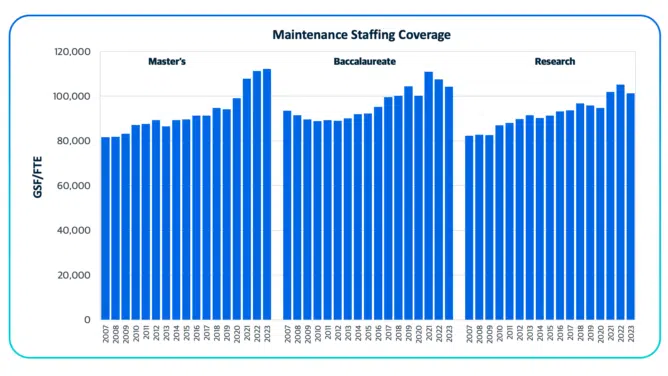

While academic communities strive to minimize budgetary pressure on staffing, the long-term trends toward operating with fewer people in higher education continue. These trends exist across all segmentations of the dataset. Since 2007, the maintenance trades have experienced a coverage area increase of nearly 25%. Today’s higher ed trades worker is expected to cover nearly 106,000 gross square feet (GSF). A similar expansion of more than 22% has been seen in custodial coverage, reaching more than 41,000 GSF. Coverage areas vary from public to private institutions, with greater pressure on employees in the public sector. Notably, public maintenance workers are being asked to extend by 32% to more than 111,000 GSF. This represents a potential risk that must be carefully reviewed on a campus-by-campus basis.

We have noted before that these escalations in coverage area are being aided by advancements in technology to monitor and deliver maintenance services. The use of enhanced monitoring can reduce human time in the field to check systems, and improved equipment technologies can reduce labor demands on services like floor care. But we are also aware that staffing challenges are leaving schools shorthanded.

In a Gordian survey conducted in January of 2024, 61% of respondents indicated that they were facing vacancies in more than 5% of their staff positions. With fewer people delivering the work, a decline in the quality of services delivered and an increase in risk to campus programs is not necessarily inevitable, but likely. This year’s inspection scores confirm that this is the case for at least some campuses already. Higher education is an enterprise dominated by the contributions of its people. The public thinks often of the contributions of the faculty and students to the educational practice, or the athletes we watch on fields and courts that captivate our passions, and perhaps even the alumni who make astonishing financial gestures as gratitude for what the institution has done to jettison their careers. That centrality is no different in the facilities realm where the people with the technical and cultural knowledge to serve the various needs of these communities underpin the success of all those using the campus. A vulnerability here not only risks the success of facilities stewardship and services today but, over the long term, also endangers the assets that are their primary professional focus. This staffing challenge deserves further review.

When asked, almost to a person facilities leaders cite the challenge to find staff as one of their top concerns. Often it is at the top of the list. Despite all the new diagnostic tech, the organizational tools, the more durable materials/systems and the reduced post-pandemic service levels, facilities organizations are still fundamentally reliant on people to do work in the three-dimensional world.

The average age of trades workers has been rising for a long time and it shows no signs of decline. In July 2023, Nick Jones from Classet, an organization focused on addressing the blue-collar skills gap, noted that “the average age of someone working in skilled trade careers today is around 55, [compared with] the average age of all working Americans, which is 44.” A networking coach and public speaker with more than 25 years of experience in the architecture, engineering and construction industries, Julie Brown, points out that according to the National Center for Construction Education and Research, an estimated 40% of current building industry workers will retire by 2030.

Trades work is hard on the human body and the productivity of a trades worker can fade over time. It follows, then, that the productivity of facilities organizations shrinks at a similar rate. Moreover, it is harder and harder to find replacement workers as fewer people join the trades.

It is important to note the challenges include promoting and retaining workers at all levels. Consider this from “How to Succeed Quickly in a New Role,” an article published in the Nov-Dec 2021 Harvard Business Review:

“Gartner surveys indicate that a full 49% of people promoted within their own companies are underperforming up to 18 months after those moves, and McKinsey reports that 27% to 46% of executives who transition are regarded as failures or disappointments two years later. They have the right skills and experience. They understand the company’s goals. They’ve been vetted for cultural fit. So why didn’t they quickly excel in their new roles?”

Much has been written about helping executives grow and succeed, but less so about the rest of the workforce. It is not enough to give people a growth path, they must have and develop the correct skills to succeed. Those in the trades receive a lifetime’s worth of training in specialized, technical work. Typically, they do not receive as much training in the “soft” skills necessary for thriving within a corporate structure. Closing the soft skills gap will enable institutions to maintain continuity in their facilities workforce and, by extension, continuity in facilities performance.

Institutions are employing a number of different strategies to find and keep people, starting with retaining current staff by creating a culture they find appealing and viable. APPA is helping by expanding its most important area of impact on the industry, training and development. Known inside higher education and beyond for professionalizing facilities leadership, APPA has recognized the importance and value in programs to address individual contributors, from their Leadership Academy and Institute for Facilities Management to the Supervisor’s Toolkit.

The new Invest in Success program is designed to inspire and develop front line staff. A non-technical training program, the program connects them to the skills for cultivating their own long-term success and that of the institution that employs them. Michelle Friedrick, Senior Director of Talent Development at American University and the architect of the program notes, “One of the key reasons people leave is challenges with relationships amongst their co-workers. Critical to successful team relationships is strong communication and a sense of trust.” One of the places it is being implemented early is at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

According to Margaret Tennessen, Deputy Associate Chancellor at UW-Madison’s Division of Facilities Planning & Management, “We have long provided technical training. This program is providing training for front line employees in the human skills that folks need in the workplace to have difficult conversations, resolve conflict, bridge differences and understand that all of us thinking alike isn’t necessarily a good thing…if you don’t get along with co-workers, get along with your boss, you become disengaged and more likely to leave.” The program has been offered three times so far. Not only has there been robust enthusiasm expressed by participants, one group has asked to continue meeting to further develop and practice the skills that they have learned. These people appreciate the investment being made in them.

Key to this program is the idea of helping people grow. “Communication is a two-way street. This program helps everyone develop the skills to share and listen thoughtfully. This is especially important for younger employees who are asking how we invest in our staff, what they will learn and how they will grow,” says Friedrick.

Technology can act as a workforce multiplier, an asset to the boots on the ground

In the face of staffing challenges, leveraging emerging technologies can make the workforce smarter and more productive. Mark Helms, AVP of Facilities Services at the University of Florida cites numerous approaches his department is undertaking to expand the reach of teams in the field. “We are using autonomous floor care and mowing equipment where it makes sense, but facilities campuses are complicated places that require flexibility so our staff can deliver. Simply moving to battery-powered vacuums allows housekeepers to cover about three times the area, since they don’t have to work around the cords or stop to ensure no one trips over the cords, let alone move to a new outlet every few minutes.” The university is embracing innovation in ways that go beyond new tools.

“We are using sensors to monitor levels for paper towels, toilet paper and other bathroom supplies,” Helms says. “It is helping to eliminate unnecessary trips to low-use bathroom areas and increasing the productive time of our people. They can focus on the areas that need attention and improve the experience for all the people who are using our facilities.”

Introducing new technology into the workplace often invites tension, as employees, many of whom view themselves as productive and efficient, resist learning to work with a new tool and fear being replaced by it. Institutions of higher education are no exception to this tension. But it need not be a fact of life. As leaders at the University of Florida and elsewhere have demonstrated, when properly integrated into ongoing operations, technology can act as a workforce multiplier, an asset to the boots on the ground. These new tools aren’t replacing human employees; they’re making them better.

Retaining existing staff is its own challenge. What about finding new employees? Using the reference points of Nick Jones and Julie Brown above, the big challenge soon will be replacing the workers leaving the workforce. With less new talent coming into the industry, college towns are slowly dwindling in candidates with all the key skills. John Shenette, formerly Vice President for Facilities and Campus Services at Wake Forest University and now Vice President at CSL Consulting notes that, “More and more, even if the potential employee has the technical skills, and that is a big if, there is a disconnect with the personality and behavioral needs, the soft skills for working in an educational community. And often, given what schools are willing to pay, those with the necessary technical skills are going elsewhere, anyway.”

While wage and salary levels for higher education facilities workers have long been a problem, there has been a lot of movement there, at least at the lower end of the range, with many states and even individual institutions making recent increases to the minimum wage. Only seven states now rely on the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour and as of January 2024, there are seven states at or above $15 and seven more proposed to follow them in the next several years. This hasn’t addressed all of the issues, but it has helped institutions retain employees who were leaving for bumps of even $0.50 just to put more money in their family’s pockets.

“Younger employees…are asking how we invest in our staff, what they will learn and how they will grow,” Michelle Friedrick | Senior Director of Talent Development, American University

One key challenge that continues for those looking for local talent is the long hiring timeline in some campus cultures. This process has merit, considering it was designed to carefully vet faculty who will be around for decades and staff members who must navigate and preserve the complex relationships existing on college campuses. But when competing for talent in relatively low dollar positions, a long process will always lose out to the need for a paycheck. In that January 2024 Gordian survey, 85% of respondents indicated that the hiring timeline was six weeks or greater, with 38% reporting hiring timelines greater than three months.

At the University of Mississippi, Director of Facilities Management Dean Hansen notes, “When (restaurant chain) Zaxby’s is paying $17 for a custodial position and the college is paying $14, time is of the essence if you are going to entice them to join a great culture.” It has taken five years, but outside of custodial, Hansen has every position filled. Key to that success has been the creation of a desirable working community with highly competent leaders on the front line, and front line workers who are supported and encouraged to contribute. Within that culture, wage gaps are closing and hiring times are accelerating, giving Hansen hope he can keep those roles filled.

Institutions have long relied on executive search firms to assist them in finding senior leadership positions, but that support is now needed deeper in the organization. Classet is working to build connections between employees and employers in a market where it is ever harder to find the talent needed to address critical blue collar work needs. At the University of Mississippi, Hansen is turning to outside organizations to help him find front line technical help. He is exploring work with Aerotek, a national placement firm with areas of focus in construction, energy and industrial products to help him find the talent he needs. “They will source the talent and provide me with the skills I am having difficulty finding locally,” Hansen says.

Hansen is also finding early success with internship programs connected to community college and high school job corps programs. “Participants from the program we have with Northwest Mississippi Community College had the chance to get to know our team and each other. Even with competitive offers elsewhere, they wanted to stay on with us because they knew us and saw the potential for themselves long term.” Such programs create experiences that help young employees realize the benefits and opportunities associated with being connected to these kinds of institutions.

Facilities organizations and their HR colleagues on campus are exploring strategies to fill job openings and retain the people in place. Success in both respects will be necessary for facilities organizations to adequately meet the needs of their communities today and in the years ahead. Unfortunately, finding and keeping talent is as complicated as it’s ever been. Campus leaders need to be prepared to meet new sets of expectations, including:

- Looking farther, harder and in different places to find skilled staff.

- Developing existing talent, even if it means inventing programs from whole cloth and administering them on their own.

- Investing in your staff’s cultural and social skills so they not only stay but grow.

Since 1983, it has become a tradition for Presidents closing their State of the Union address to assure those listening that the state of the union is strong. It is an expression of confidence in the nation, no matter the challenges being faced. As we close this edition of the State of Facilities in Higher Education, it can be said that the state of the higher education facilities industry is strong. This strength is derived from campus leaders’ widespread awareness of and willingness to confront complex challenges. It is strong because there is robust data about the industry’s current hurdles and schools are committed to gathering more. Lastly, the state of higher ed facilities is strong because the community is readily sharing ideas, insights and solutions.

As a community, we must acknowledge that strength is not the same as invulnerability. There are places across higher education where facilities and entire institutions are at risk. But where people are aware of the challenges and willing to make the difficult choices, by and large there is great promise for the future.

Yet this promise will go unfulfilled if we fail to attract and retain a workforce dedicated to enhancing the physical campus. The pool of potential employees is drying up. Competition for skilled labor is heightening. As stewards of higher education, institutional leaders from across the U.S. must collaborate on solutions for making the facilities field more for people to enter and remain in.

At Gordian, we recognize that it is a privilege to serve these institutions and this community. We are grateful to have this opportunity to share our observations and look forward to continuing to assist you as you forge your unique paths into the future.

Harnessing the Power of Benchmarking: The Edge Your Institution Needs for Campus Planning

State of Facilities Reflections

Campus Reimagined: Leading Higher Ed Facilities and Finance Into a New Era

College Uses Data-Driven Assessments To Save Energy and Improve Campus

Finance, Facilities and Planning: Rethinking the Framework for Collaboration in Higher Ed

Share this: